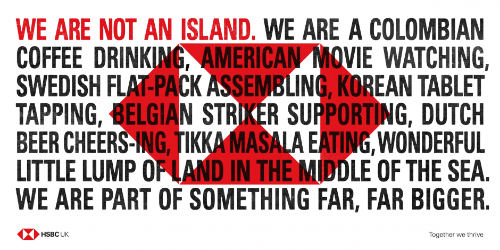

In the marketing echo chamber, it can be easy to get disenchanted with your role. Nowadays if your hair gel, extruded potato snack or toothpaste is not involved in some planet-saving endeavour or fight for human rights, then the zeitgeist implies we should be asking ourselves ‘why do we bother’.

Kotler identifies six categories of brand activism, together with some examples of causes under each.

- Social activism includes areas such as equality – gender, LGBT, race, age, etc. It also includes societal and community issues such as education, school funding, etc.

- Legal activism deals with the laws and policies that impact companies, such as tax, workplace, and employment laws.

- Business activism is about governance – corporate organisation, CEO pay, worker compensation, labour and union relations, governance, etc.

- Economic activism may include minimum wage and tax policies that impact income inequality and redistribution of wealth.

- Political activism covers lobbying, voting, voting rights, and policy (gerrymandering, campaign finance, etc).

- Environmental activism deals with conservation, environmental, land-use, air and water pollution laws and policies.

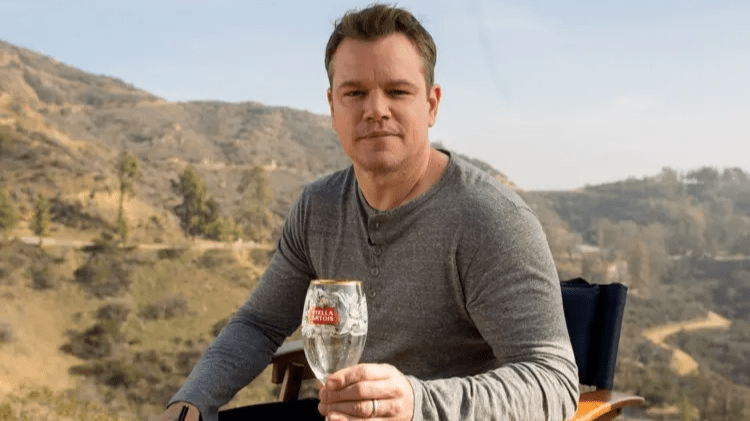

Several firms are noted for their activist credentials, with many more currently repositioning themselves to participate more fully. Here are a few examples.

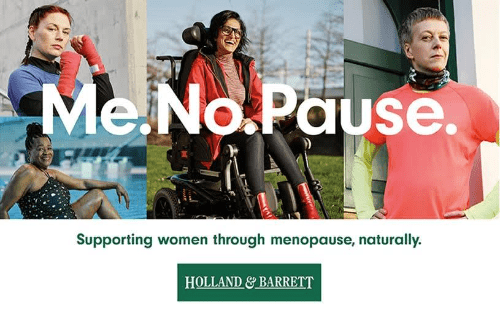

Holland & Barrett – the health food store chain, has just launched its “Me. No. Pause” campaign. The retailer is seeking to support menopausal women. The campaign which discusses a taboo subject and talks to an “undervalued” middle-aged female audience, recently won £500k of free media in the inaugural Transport for London (TfL) diversity competition (although H&B had planned to run it anyway).

The arguments for and against

This is all fine and dandy, but perhaps the key question for marketing leaders is should my brand(s) be taking a more activist approach? Below I look at some of the arguments for and against.

IN FAVOUR

- Standing for something can build equity. Becoming synonymous with a cause can be a more durable way to build distinct brands than relying on differences in product benefits; especially in categories where it’s difficult to be different. Typically, more emotive advertising (versus functional) gets better diagnostics.

- It helps teams make choices. In complex organisations and markets, having a strong values ‘compass’ should help employees at all levels to make better, more consistent decisions.

- Activism can be cost-effective. If the issue resonates with the target consumer, the brand can achieve fame ‘organically’ via social media with little or no media spend.

- It’s easier to recruit & engage talent. A purpose beyond profit matters much more to today’s employees and in effect can be a part of the non-monetary benefits package.

- Activism can achieve societal results. It is highly likely that vocal global business leaders have helped create more momentum behind some issues (like sustainability) than would otherwise be the case.

- It’s worked before. You could argue brand activism has been around since the industrial revolution. For example, much of the UK confectionery business has its roots in Quakerism (Cadbury of Birmingham, Rowntree’s of York, and Fry’s of Bristol) and long before social housing and the welfare state existed they were pioneering improvements in living and working conditions for communities.

AGAINST

- You must make choices. If you talk about brand purpose in marketing communications, then you don’t talk about your product or service (as much). The more single-minded the marketing message, the more effective it will be.

- Financially unproven. Studies used to show purpose as being ‘inseparable’ with profits (e.g. the 10-year Stengel 50 study) are controversial, chiefly because correlation doesn’t prove causality (e.g. firms tend to champion purpose with brands that already receive greater investment).

- Consumer importance over-stated. It’s easy to find stats suggesting that consumers like brands that align with their values and will boycott brands that don’t, but these are nearly always ‘claimed’ in research. Most FMCG purchases are nonconscious, so does activism really change behaviour in the store aisle or online?

- Inauthenticity. There are some well-publicised failed attempts to champion causes (Starbucks on race relations) where they’ve come across as superficial or perhaps only spuriously related to the brand. Recently Dutch historian Rutger Bregman became an unlikely poster boy. He caused a storm at Davos by challenging what he sees as the collective “hypocritical hand-wringing” of CEOs who wax lyrical about societal problems but pay little or no corporate tax.

- Inviting scrutiny. Public and regulatory scrutiny of companies is a good thing. But making a stand in one area invites scrutiny in others. For example, is a brand’s social activism undermined if its owners off shore profits and indirectly make less money available for state-funded social provision?

- Lazy marketing? Behavioural scientist Richard Shotton asks if our current obsession with purpose/activism is because we’ve simply fallen out of love with marketing and are ignoring the core tenets of the trade. Brand activism is just one tool in the marketer’s toolkit.

Triple bottom-line

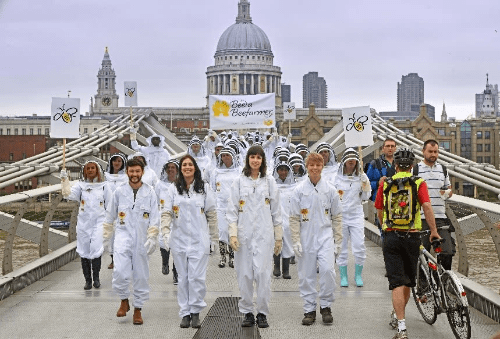

One brand doing it well is Rowse honey. Under the banner of “Hives for Lives” this leading spread brand has been working for several years to increase the bee population through sponsorship of bee-keeping programmes and scientific research.

It’s easy to see how the brand is driving the so-called triple bottom line – where the interests of people, plant and profit coincide. What’s more it just makes sense and is a far-cry from the fuzzy or contrived stances of some other brands.

- People – Rowse creates apprenticeships for school leavers, providing a route to employment and the programme also has a positive impact on its employees’ motivation.

- Planet – the decline of bee populations and the associated threat to nature is now well-documented, their decline is a key ecological issue which the firm is tackling.

- Profit – strengthening the honey supply chain has an obvious commercial value to the UK’s largest purchaser of the raw material.

The decision whether – or perhaps more importantly, how – to use ‘brand activism’ is an individual one. Leaders need to ask themselves –

- Which consumers, and how many, will care about our activism? What are the risks of alienating others?

- Will our commitment to a cause be credible and real?

- Does it make financial sense – will consumers care enough to pay more for our brand?

- Do we have the right governance & leadership support in place to make this work?

- Does this matter to our workforce? Will it improve engagement?

Well-conceived and authentic brand activism is right for some brands. But, making a holistic and enduring commitment to improve the enterprise’s social & environmental impact is surely more helpful to stakeholders in the long run. The problem with that approach of course, is that it doesn’t feel as new, grab headlines or sell many books.